Are Batteries AC or DC Current?

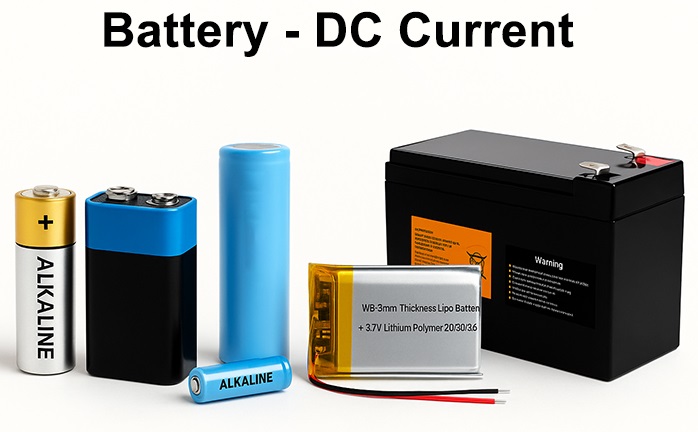

When people first search for are batteries AC or DC current, they’re usually trying to understand how electricity actually moves inside a cell. The simple answer is that all chemical batteries deliver DC current, not AC. Whether it’s a small AA cell, a phone battery, or even a car battery, the energy stored inside the chemistry can only push electrons in one direction, which is why terms like direct current battery describe their operation accurately.

This also explains the follow-up question many people have: car battery current AC or DC? Just like any other electrochemical cell, a car battery outputs DC only—the vehicle’s inverter and alternator are responsible for generating or converting AC when needed.

You may also see people searching for alternating current battery, but this type of battery simply does not exist in practical engineering. A battery cannot naturally alternate its polarity on its own; any AC output must come from an external inverter, not the battery cell itself. In short, batteries are fundamentally DC devices, and AC only appears after additional electronic conversion.

What Creates an Electric Current in a Battery?

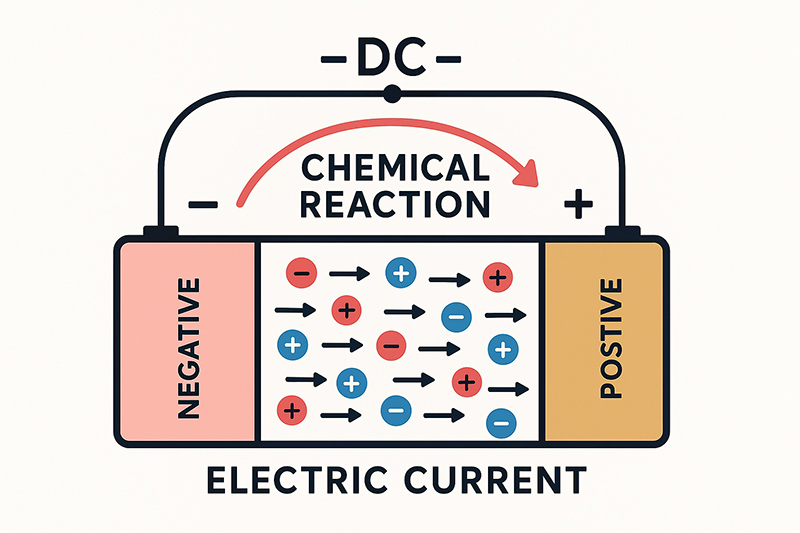

Batteries push current because the chemical reactions inside them create a voltage difference between the positive and negative terminals. That voltage acts like an “electric pressure” that makes electrons want to move from one side of the cell to the other. Inside the battery, two different materials (the anode and cathode) sit at different chemical energy levels. As the battery discharges, reactions at the anode release electrons, while reactions at the cathode take electrons in. This separation of charge is what creates the voltage that can drive an electric current through any closed circuit you connect.

When you hook a battery up to a load, such as an LED, a motor, or a phone, that voltage finally has a path to “push” electrons. Electrons flow from the negative terminal, through the external circuit (doing work in your device), and return to the positive terminal. In modern lithium-ion cells, this process happens at a relatively high voltage: their nominal voltage is typically around 3.6–3.7 V per cell, which is why packs made from several cells in series can easily power laptops, ebikes, and power tools. Inside the cell, lithium ions move through the electrolyte from anode to cathode, while electrons move outside the cell through the circuit; together, these linked movements create a steady direct current (DC).

So what creates an electric current in a battery is not “stored electricity,” but ongoing chemical reactions that maintain a voltage difference. As long as the chemistry can keep that voltage up and the circuit is closed, the battery will continue to produce current. Once the reactants are used up and the voltage falls too low, the battery can no longer push electrons effectively, and the current drops off—that’s when we say the battery is “dead.”

How Does Battery Current Flow?

When a battery produces current, it pushes electrons in a single, consistent direction—because all chemical batteries output DC current, not AC. The flow may sound simple, but the direction often confuses people.

Electrical current in a battery flows from the negative terminal to the positive terminal on the electron level, because electrons carry a negative charge and naturally move toward the positive side. This electron movement is what actually produces current in any chemical cell.

But here’s the twist:

In circuit diagrams and textbooks, “conventional current” is defined the opposite way—from the positive terminal to the negative terminal. This definition was created before electrons were discovered, and we still use it today for consistency.

So in reality, we have two directions describing the same thing:

Electron flow: negative → positive

Conventional current flow: positive → negative

Both describe how a battery produces current, just from different viewpoints.

What matters practically is that a battery—whether you are talking about lithium battery current or the output of a simple AA cell—always sends its current outward through its positive terminal and returns through the negative—the one-direction, closed-loop movement that makes LEDs light up, motors run, and phone chargers actually charge. No matter whether it’s a 1.5 V AA battery, a 12 V lead-acid car battery, or a lithium-ion pack in an ebike, the direction is the same. If the electrons ever reversed direction, you wouldn’t have DC anymore.

Current Limitations: Max Discharge Current and Charging Current for a Battery

Every battery—no matter if it’s a tiny AAA cell or a large car battery—has two important limits: how much current it can output, and how much charging current it can safely accept. This is what engineers usually call the current limitation. Exceed it, and the battery heats up, ages faster, or in the worst cases, suffers permanent damage.

Small household batteries such as 1.5V AA or AAA alkaline cells typically deliver only modest current—often under 1A—because their chemistry isn’t designed for high drain. Even the common 9V rectangular battery can only supply a few hundred milliamps before its voltage collapses. These cells work well for remote controls or clocks, but “how much current” they can handle is limited by design, not voltage.

Move up to 12V systems, and the picture changes. A 12V lead-acid battery, like those used in cars, can output hundreds of amps during engine starts. But its charging current is still limited; most automotive chargers stay within 10–30A to protect the plates from sulfation and overheating. Lead-acid batteries can deliver huge bursts, but they dislike aggressive charging.

Modern lithium batteries, including lithium-ion, lipo packs, and cylindrical cells like the popular 18650, have much more defined and predictable current specifications. A typical 18650 cell may offer 5A to 20A of max output current depending on whether it’s optimized for capacity or high-drain performance. Charging current, however, stays lower—usually around 0.5C to 1C—to preserve cycle life. This is why a li-ion or lipo pack may power a drone or an e-bike controller with high currents, yet still require slow, controlled charging.

Even within the same voltage category, such as 3.7V lithium batteries, the limits vary by chemistry and internal design. High-power versions can output high bursts, while energy-dense types prioritize runtime over amperage. Understanding these differences helps users avoid the common mistake of assuming “more volts means more current”; in reality, chemistry and internal structure matter far more than voltage alone.

So whether it’s a tiny AAA or a heavy car battery, every chemistry has a carefully engineered current window. Staying within that window—both on discharge and charging—keeps the battery cooler, safer, and significantly longer-lasting.

Battery Current Calculation: How to Calculate Battery Current

When people talk about “how much current” a battery can handle, they often forget that current is not random—it follows predictable electrical rules. Engineers rely on basic principles such as the current formula (I = P ÷ V) to estimate how much current a device will pull from a battery pack. For example, a 100W motor running on a 24V battery pack typically draws around 4–5A. This is why understanding current draw is essential: devices never pull the same current, and the battery doesn’t “push” current; the load determines it.

To make things simpler for non-engineers, many technicians use a charging current calculator or current draw calculator when designing small packs, especially for DIY e-bike batteries, RC lipo packs, or custom lithium-ion modules. These tools help estimate safe charging current, expected discharge current, and whether a battery pack is being overloaded. They don’t replace real-world testing, but they prevent obvious mistakes—like charging a 2Ah lithium cell at 5A or connecting a low-drain AA battery to a high-power device.

Current measurement plays an equally important role. Using tools like a multimeter or clamp ammeter, engineers measure the real-time current flowing into or out of a battery pack. This matters because datasheet calculations rarely match real usage: voltage sag, internal resistance, and load spikes all change the actual current. A battery pack for an e-bike may be rated for 30A continuous, but short acceleration peaks can temporarily exceed that. Without proper current measurement, these peaks are invisible—and they shorten battery lifespan.

When building or selecting any battery pack—whether it’s for a flashlight, a scooter, or an industrial machine—paying attention to charging limits and current draw ensures you’re not pushing the cells beyond what they’re designed for. A well-balanced pack isn’t just about voltage and capacity; it’s about matching current capability with the intended device so the battery runs cooler, safer, and lasts significantly longer.

Why Short-Circuit Current Is So Dangerous—and How Batteries React to It

Among all battery-related electrical parameters, short-circuit current is the one that engineers fear the most. Unlike normal discharge, where the load controls how much current flows, a short circuit removes all resistance in the circuit. The battery suddenly tries to dump its entire stored energy at once, creating a surge that can reach hundreds or even thousands of amps depending on the battery type and size.

This is why even small cells—like AA, AAA, or a 3.7V lithium-ion—can become dangerous if their terminals are accidentally bridged by a metal object. The rapid rise in current produces intense heat, and in larger packs, it can trigger thermal runaway or melt wiring within seconds. Car batteries and lead-acid systems are even more extreme; their short-circuit current can be high enough to vaporize metal tools or weld contacts together.

Modern lithium-ion battery packs use multiple layers of protection to prevent short-circuit hazards, including BMS cutoff circuits, internal PTC resistors, and CID vents in cylindrical cells. However, no protection is perfect. If the short occurs outside the battery—such as crushed wiring, damaged connectors, or exposed metal—the protection circuit may not activate in time.

In practical terms, this means a battery pack’s “normal” current capability (like 10A, 20A, or 50A) is completely different from its short-circuit current, which can be 20–100 times higher. Understanding this gap is essential for anyone designing, repairing, or using battery-powered devices. Good insulation, proper fusing, and safe wiring practices are what prevent a minor contact failure from turning into a catastrophic event.

Conclusion

All battery current is direct current (DC): the electrons move in one steady direction through the external circuit, never alternating back and forth like AC from the grid. A battery can produce this current only because chemical reactions inside its cells continuously separate charge and maintain a voltage between the positive and negative terminals. Every chemistry—whether it’s alkaline, lead-acid, NiMH, or a lithium battery—has a maximum safe current it can deliver, set by its design, internal resistance, and thermal limits. In real-world use, it’s critical to stay within those limits and to avoid any kind of short circuit, because a short can force extremely high current to flow, overheating the cells, damaging the pack, and in severe cases even causing fire or thermal runaway.